Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

The year 1804 marked the culmination of the most successful slave rebellion in world history. After 13 years of revolutionary warfare against the mightiest colonial powers of the era, the formerly enslaved people of Saint-Domingue achieved what many thought impossible—they defeated Napoleon Bonaparte’s forces and established Haiti as the world’s first Black republic. This unprecedented victory shattered the foundations of the Atlantic slave economy and challenged the racist underpinnings of European imperialism.

In the aftermath of this world-altering revolution, Haiti’s leadership faced the monumental task of nation-building amid hostility from surrounding slave-holding powers. The new nation stood isolated, threatened by potential re-invasion, and burdened with the challenge of transforming a plantation economy based on brutal exploitation into a system that could sustain freedom and independence.

Jean-Jacques Dessalines, a formerly enslaved man who rose through military ranks to become the revolutionary army’s commander-in-chief, initially took the title of Governor-General after declaring independence on January 1, 1804. Yet by February 1804, Haiti’s military leadership had already begun the process of transforming the governance structure, culminating in Dessalines’ elevation to Emperor in September of that year.

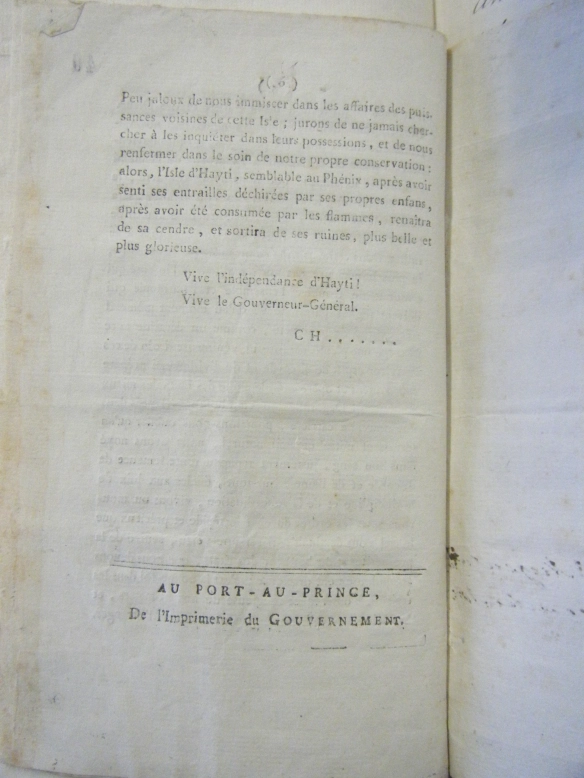

The document before us—the nomination of Dessalines as Emperor on February 15, 1804—represents a critical turning point in Haiti’s post-revolutionary trajectory. It reveals the complex political philosophy that guided Haiti’s founding leaders and their pragmatic assessment of what governance structure might best secure their hard-won freedom against internal division and external threats.

Colonial powers and their historians have systematically distorted the meaning of Haiti’s imperial turn. For centuries, Western narratives portrayed Dessalines’ elevation to Emperor as evidence of Black leaders’ supposed inability to maintain republican governance—a deliberate mischaracterization designed to delegitimize Haiti’s revolution and justify ongoing isolation and exploitation.

These narratives deliberately ignored the geopolitical reality facing the new nation. Haiti existed in a hemisphere dominated by monarchies and colonial powers, with the United States still firmly entrenched in slavery. The revolutionary leaders understood that internal division had repeatedly threatened their struggle for freedom, most notably when Toussaint Louverture was betrayed and captured. The decision to establish a centralized imperial authority wasn’t a rejection of democratic principles but a strategic adaptation to secure national survival.

Western historiography also conveniently obscured that Haiti’s imperial model followed contemporary European precedents—Napoleon himself had crowned himself Emperor of France just months earlier in December 1804. Yet while European monarchies were portrayed as sophisticated political systems, Haiti’s adoption of similar structures was characterized as mimicry or evidence of political immaturity.

This erasure extends beyond academic discourse. The deliberate misrepresentation of Haiti’s early governance choices formed part of a broader campaign to isolate and undermine the world’s first Black republic—a campaign that included France’s 1825 indemnity demand forcing Haiti to pay the equivalent of $21 billion in today’s currency for the “property” (enslaved human beings) that France had “lost.”

The nomination document reveals sophisticated political thinking that challenges colonial caricatures. Three key aspects deserve particular attention:

Unity as Survival Strategy

The text explicitly states that “supreme authority does not allow for division” and cites “cruel experience” to argue that a people “can only be properly governed by a single person.” Far from naive autocratic impulses, these statements reflect hard-learned lessons from the revolution itself. Multiple times during the struggle, internal divisions had threatened to derail independence. The generals who signed this nomination—including Henri Christophe and Alexandre Pétion who would later divide Haiti—recognized that external threats demanded internal cohesion.

Rejection of Colonial Subordination

The document pointedly rejects the title “Governor-General” because it “implies a secondary power dependent on some authority whose yoke we have forever shaken off.” This reveals acute awareness that titles and governance structures carried symbolic weight in international relations. The imperial title represented not a mimicry of European forms but a declaration of equal sovereign standing—Haiti would not be governed as a “commonwealth” or subordinate territory but as a fully independent power.

Popular Legitimacy

While establishing a monarchy, the document repeatedly references “the strongly pronounced will of the people of Haiti” and “the general wish.” This seemingly contradictory emphasis on popular consent alongside imperial authority reflects the complex revolutionary ideology that emerged from Haiti’s struggle. Power derived not from divine right or hereditary privilege—as in European monarchies—but from the will of citizens who had fought for their freedom.

The signatories include figures like Alexandre Pétion and Henri Christophe, who would later represent competing visions for Haiti’s future. Their unity in this moment speaks to the perceived necessity of centralized leadership in the immediate aftermath of revolution, even among those who would later advocate for different systems.

The tensions embedded in Haiti’s imperial turn continue to resonate in post-colonial societies worldwide. Nations emerging from revolutionary struggles or colonial domination often face the dilemma of balancing idealistic governance models with pragmatic security concerns. From Thomas Sankara’s Burkina Faso to post-apartheid South Africa, revolutionary movements have grappled with how to secure transformative gains while defending against counter-revolutionary forces.

Haiti’s experience highlights the double standard applied to formerly colonized nations. When European powers adopt authoritarian measures in times of crisis, they’re portrayed as reluctant necessities; when formerly colonized people do the same, they’re characterized as inherently incapable of democratic governance. This asymmetric judgment continues to shape international responses to political developments throughout the Global South.

The document’s emphasis on securing “the guarantee and safety of citizens in an immutable and irrevocable manner” speaks to a fundamental challenge that persists today: how to establish governance systems that can withstand both internal division and external pressure. For Haiti, the answer seemed to lie in consolidating authority to present a unified front against hostile powers. Two centuries later, formerly colonized nations still navigate similar pressures as they assert sovereignty within a global order designed to maintain Western hegemony.

Haiti’s early governance choices also challenge simplified narratives about democratic evolution. Rather than seeing governance forms as progressing linearly from “primitive” authoritarianism to “advanced” democracy, Haiti’s experience shows how political systems respond to specific historical circumstances and security needs. This complexity demands nuanced analysis rather than reductive judgments that serve colonial narratives.

The nomination of Dessalines as Emperor calls us to engage critically with Haiti’s revolutionary legacy beyond simplistic narratives. For educators, activists, and community leaders within the global Haitian diaspora, these primary documents offer powerful teaching tools to counter the persistent myths that have surrounded Haiti’s early independence.

Digital archiving initiatives play a crucial role in making these historical documents accessible. By sharing, translating, and contextualizing primary sources like this nomination, we collectively restore complexity to Haiti’s revolutionary history and challenge narratives that have justified two centuries of intervention and exploitation.

Community education efforts should emphasize the strategic thinking behind Haiti’s governance choices rather than accepting colonial framings. Reading circles, historical podcasts, and diaspora educational programs can create spaces to engage with these documents directly, allowing people to draw their own conclusions free from colonial filters.

For scholars and writers, this document invites comparison with other post-revolutionary transitions worldwide. How do nations balance revolutionary ideals with security imperatives? What governance structures emerge from successful resistance movements? These comparative approaches situate Haiti’s experience within global patterns rather than treating it as exceptional or pathological.

Most importantly, this history challenges us to question contemporary power structures. The principles articulated in this nomination—national unity, rejection of subordination, and guarantee of citizens’ safety—remain relevant to Haiti’s ongoing struggles for true independence from external control. By reclaiming this complex history, we strengthen our capacity to imagine and create governance systems truly free from colonial influence.

The nomination of Dessalines as Emperor reveals the complex reality of nation-building after revolution. Far from a simple power grab or mimicry of European forms, Haiti’s imperial turn represented a strategic adaptation to secure newly won freedom in a hostile world. The document’s emphasis on unity, security, and rejection of subordinate status reflects the revolutionary leadership’s pragmatic assessment of what governance structure could best protect their unprecedented achievement.

Colonial narratives have deliberately mischaracterized this choice to delegitimize Haiti’s revolution and justify two centuries of intervention. By engaging directly with primary sources like this nomination, we reclaim the sophisticated political thinking that guided Haiti’s founding generation.

The tensions within this document—between centralized authority and popular will, between revolutionary ideals and security imperatives—continue to resonate in post-colonial societies worldwide. Haiti’s experience offers not a template to be copied but a complex case study in how revolutionary movements navigate the treacherous waters of post-colonial nation-building.

As we confront today’s challenges, Haiti’s revolutionary leaders offer not just inspiration but practical wisdom. Their attempt to build governance systems that could withstand both internal division and external pressure speaks directly to the ongoing struggle for true independence from colonial and neo-colonial control. By reclaiming this history in all its complexity, we honor their legacy and strengthen our own capacity to imagine and create truly liberated futures.

1. Why did Haiti’s revolutionary leaders choose to establish an empire rather than a republic?

The nomination document cites the need for unity, security, and international recognition. Having experienced how internal divisions threatened the revolution, they believed centralized authority would better secure their independence against external threats.

2. How did colonial powers distort the meaning of Haiti’s imperial turn?

Colonial narratives portrayed it as evidence of Black leaders’ inability to maintain republican governance, deliberately ignoring the strategic rationale and similar governance choices in Europe (like Napoleon’s coronation).

3. What does the document reveal about the political philosophy of Haiti’s founding leaders?

It shows sophisticated understanding of governance challenges, emphasizing popular legitimacy while recognizing security imperatives. The rejection of the “Governor-General” title specifically challenged colonial hierarchies.

4. Who were the key figures who signed this nomination?

Signatories included Henri Christophe and Alexandre Pétion—who would later represent competing visions for Haiti’s future—demonstrating their initial agreement on the necessity of centralized leadership.

5. How does Haiti’s post-revolutionary experience compare to other nations emerging from colonial rule?

Haiti’s imperial turn highlights common tensions between revolutionary ideals and security concerns that have affected many post-colonial states, challenging simplified narratives about democratic evolution.

6. What happened after Dessalines became Emperor?

Dessalines ruled until his assassination in 1806, after which Haiti divided between Christophe’s northern kingdom and Pétion’s southern republic, revealing the ongoing tensions between different governance visions.

7. How does this history connect to Haiti’s contemporary challenges?

The principles articulated in this nomination—national unity, rejection of subordination, and guarantee of citizens’ safety—remain relevant to Haiti’s ongoing struggles for true sovereignty and effective governance free from external control.