Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

The Forgotten Fighters of the Haitian Revolution: Reclaiming Erased Legacies

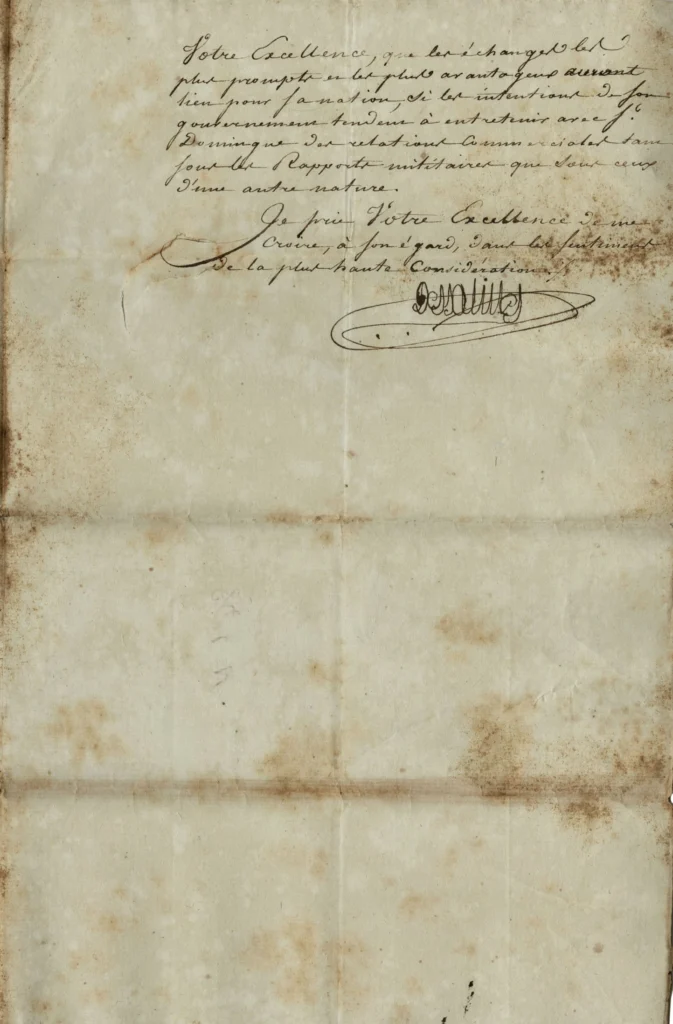

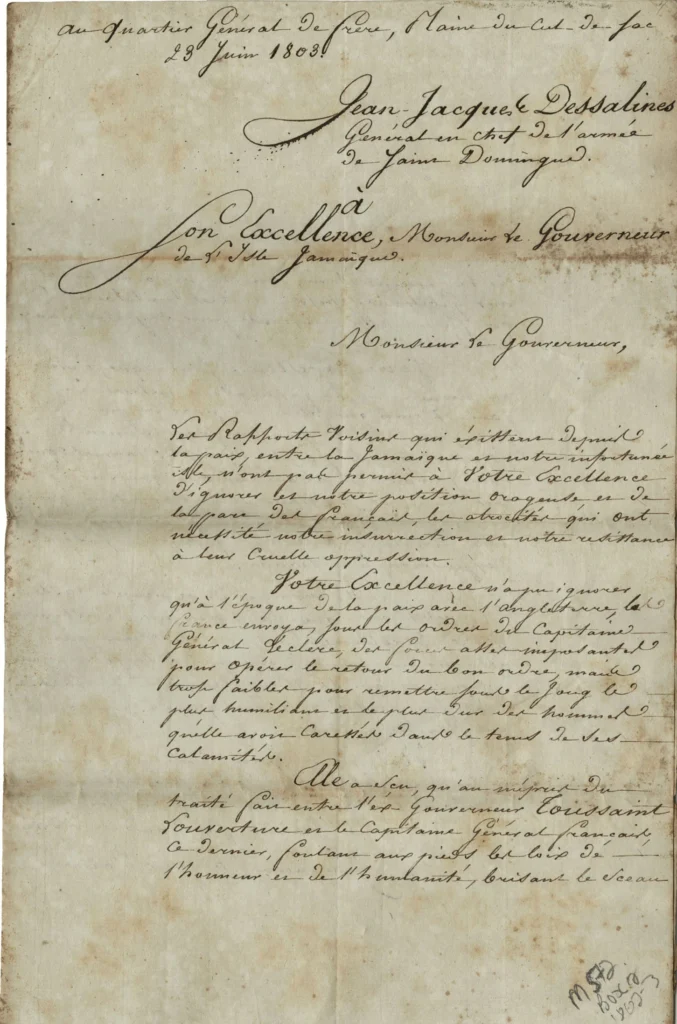

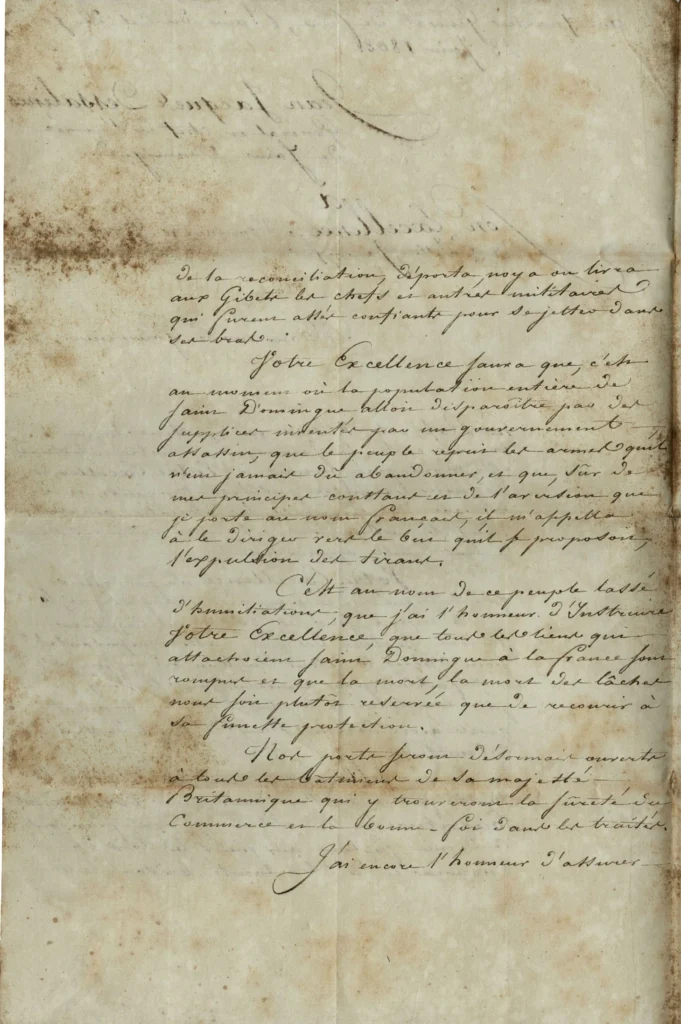

June 23, 1803. Jean-Jacques Dessalines, the indomitable leader in the final stages of Haiti’s fight for independence, addressed George Nugent, then Governor of Jamaica, in a letter of bold defiance and negotiation. Against the backdrop of colonial oppression and systemic violence, this correspondence shed light on Haiti’s resolve not only to survive but to thrive as a free Black nation.

The Haitian Revolution was more than a singular event—it was a global rupture, the first and only successful revolution fought and won by enslaved people to overthrow a colonial power. By 1803, the visionary leadership of Dessalines and others achieved unparalleled unity in the face of towering odds, dismantling one of the pillars of European colonization. The colonies feared what Dessalines represented: the essence of Black freedom and human dignity unchained.

Dessalines himself, having served under Toussaint Louverture before taking up leadership, embodied this vision. His correspondence with European figures like Nugent reflected Haiti’s strategic brilliance, balancing diplomacy and unyielding calls for respect. As the Revolution reached its culmination—marked with the iconic Act of Independence on January 1, 1804—Dessalines symbolized a global shift. Yet, his name remains pleaded out in many narratives about freedom struggles.

Haiti’s revolution stands as a testament to the strength of collective willpower, but its story has been obscured, rewritten, and vilified since its inception. The success of this revolution sparked fear and retaliation from colonial empires who understood that a free Black republic threatened their hegemonic structures. For centuries, “silence” about the Haitian Revolution served European and American powers alike, offering subjugated populations no symbols of hope.

Western historians often stripped Dessalines, women revolutionaries like Marie-Jeanne, and maroon leaders such as François Mackandal of their roles, reducing the Revolution to a footnote defined solely by violence. Even within post-independence Haiti, elite-led governments perpetuated certain erasures, distancing themselves from Dessalines, whose populist approach was often deemed too radical.

This suppression left generations of diasporic descendants disconnected from the empowering truths of their heritage. The prevailing narratives about Haiti tended to emphasize poverty, instability, and disaster—a far cry from the audacious vision Dessalines held for the new republic.

While Toussaint Louverture often occupies global history books, Dessalines’ leadership was arguably the critical turning tide toward freedom. In the June 1803 letter to Nugent, Dessalines made clear Haiti’s intent to exist, not as a colony under softer rule, but as an entirely sovereign state. His campaigns carried brutal precision, yet his aim was always to ensure liberty for the masses, a reality underestimated or erased by Eurocentric histories.

Marie-Jeanne, a warrior by blood and conviction, was a key fighter during the Siege of Crête-à-Pierrot. While colonial history pushed women to the periphery, figures like Marie-Jeanne rejected invisibility. With her musket in hand, dressed in men’s military attire, she defended Haitian independence with unflinching courage.

Long before Dessalines and Louverture, Mackandal planted seeds of rebellion in Haiti’s foundation. His mastery of African herbal traditions and poisoning tactics disrupted plantation systems for years. Though captured, his impact reverberated, proving sustained resistance was possible.

At the Battle of Vertières, Capois-La-Mort became immortalized in Haitian lore. Charging under heavy fire despite losing his horse, his rally cry embodied the indomitable spirit that defined Haiti’s fight.

Each of these figures reveals the layered, collective effort behind Haiti’s success. These unsung heroes require reclamation—not as decorative symbols—but as integral to our understanding of freedom movements worldwide.

Two centuries later, the ghosts of 1803 still roam. Today, Haiti faces consequences rooted in colonial vengeance, from crippling debt imposed by France in 1825 to international interference that undermines sovereignty. Dessalines warned of such predatory maneuvers, foreseeing the difficulties Black nations would face in carving autonomous destinies.

Parallels to systemic oppression globally—whether in racial wealth gaps in the U.S., anti-Black immigration policies, or the marginalization of Afro-descendant communities in Latin America—highlight the continued relevance of Haiti’s revolution. Dessalines’ vision challenges us to rethink liberation as not just freedom from chains but as economic, cultural, and psychological self-determination.

For the diaspora, reconnecting to this legacy offers a map for resistance; in Dessalines’ decree, we witness the refusal to bow to systemic erasure.

History is political. To forget Dessalines, Marie-Jeanne, or Mackandal is to erase the tools of empowerment our ancestors left behind. Educators, writers, and activists bear the responsibility to amplify these truths. Share Dessalines’ letters, tell your children about Marie-Jeanne, challenge institutional silences, and build cultural pride through every medium available.

The diaspora cannot afford to wait for permission to recover the heroes who defined us. Truth-telling becomes an act of rebellion itself, reclaiming narratives that seek to diminish Haitian pride.

Reclaiming Haitian history is a sacred act—a piercing reminder that liberty is hard-won and perpetually contested. Dessalines to Nugent on June 23, 1803, encapsulated this ethos: unwavering, strategic, and rooted in dignity. Our task now is to never let silence define us again.

Dessalines and Haiti’s Revolutionaries didn’t just fight for Haiti; they fought for everyone who dared to dream of freedom. Their truth will forever shine as a beacon for justice.